As

Cass

Sunstein

points

out,

the

U.S.

Supreme

Court

was

mainly

a

single

minded

body

for

its

first

century

and

a

half

with

very

little

dissent.

There

were

occasional

dissents

and

concurrences,

probably

most

notably

Justice

Harlan’s

dissent

in

Plessy

v.

Ferguson.

Still,

the

uniformity

in

decision

making

made

discerning

the

justices’

distinct

views

quite

difficult.

This

is

what

the

history

of

unanimity

in

Supreme

Court

decision

making

looks

like

based

on

the

percentage

of

unanimous

opinions

per

term

(the

case

numbers

used

in

this

post

are

derived

from

the

U.S.

Supreme

Court

Database):

Until

the

drop

off

in

the

late

1930s

and

early

1940s,

well

over

70%

of

the

Court’s

opinions

were

unanimous. What

caused

the

stark

drop

in

unanimity?

Many

theorize

that

it

had

to

do

with

Justices

Holmes’s

and

Brandeis’s

more

frequent

dissents

pointing

the

other

justices

to

the

utility

of

this

practice.

Also,

both

the

justices

and

the

public

saw

the

Court

as

a

less

legitimate

branch

of

the

government

because

the

justices

were

not

chosen

by

the

people

and

so

the

earlier

justices

did

not

want

to

rock

the

boat

by

showing

that

there

were

holes

in

the

Court’s

analyses

which

would

be

pointed

out

by

dissents.

With

the

Court

more

empowered

several

decades

into

the

20th

century,

this

legitimacy

crisis

was

much

less

of

a

concern.

With

a

stronger

norm

of

split

decisions,

researchers

could

study

the

behavior

of

specific

justices

in

greater

detail.

An

early

work

on

the

subject

by

C.

Herman

Pritchett

was

The

Roosevelt

Court:

A

Study

of

Judicial

Policies

and

Values.

With

separate

opinions,

ideology

measures

could

be

developed

that

depended

on

justices

voting

in

different

directions

across

large

sets

of

cases.

The

quintessential

measure

that

does

this

is

the

Martin

Quinn

Scores

(MQ).

Due

to

similar

and

different

voting

behaviors,

each

judge

is

given

a

score

moving

from

liberal

(negative)

to

conservative

(positive).

The

measures

begin

with

the

1937

term

because

there

were

discernible

differences

in

the

justices’

voting

behavior

from

this

point

forward.

One

neat

component

of

the

MQ

Scores

is

that

a

score

in

one

year

is

scaled

so

that

a

score

of

(+2),

for

instance,

means

approximately

the

same

thing

as

the

same

score

in

another

year.

This

is

because

there

are

always

bringing

justices

across

these

Courts

or

put

another

way,

there

is

always

at

least

one

justice

who

straddles

Court

Eras

as

other

justices

leave

the

bench.

These

justices

who

bridge

other

justices

allow

for

comparisons

across

time.

The

variation

in

scores

over

time

looks

like

the

following:

Here,

each

color

is

a

different

justice,

and

each

dot

relates

to

a

justices

score

in

a

given

term.

One

point

to

note

is

that

the

justices’

positions

were

clearly

far

apart

in

certain

terms

like

when

Rehnquist

joined

the

Court

but

were

also

clearly

clustered

together

during

most

of

Justice

Vinson’s

tenure

as

Chief

Justice.

Supermajorities

Martin

and

Quinn

Scores

predicated

on

the

justices’

votes

underscore

when

judges

vote

like

one

another

(close

scores)

and

when

they

don’t

(scores

far

apart).

For

the

past

number

of

years

until

Justice

Ginsburg

died,

there

was

a

5-4

balance

in

the

Court

which

favored

the

conservative

direction.

This

led

to

a

high

level

of

5-4

split

votes,

especially

on

issues

the

public

found

important.

The

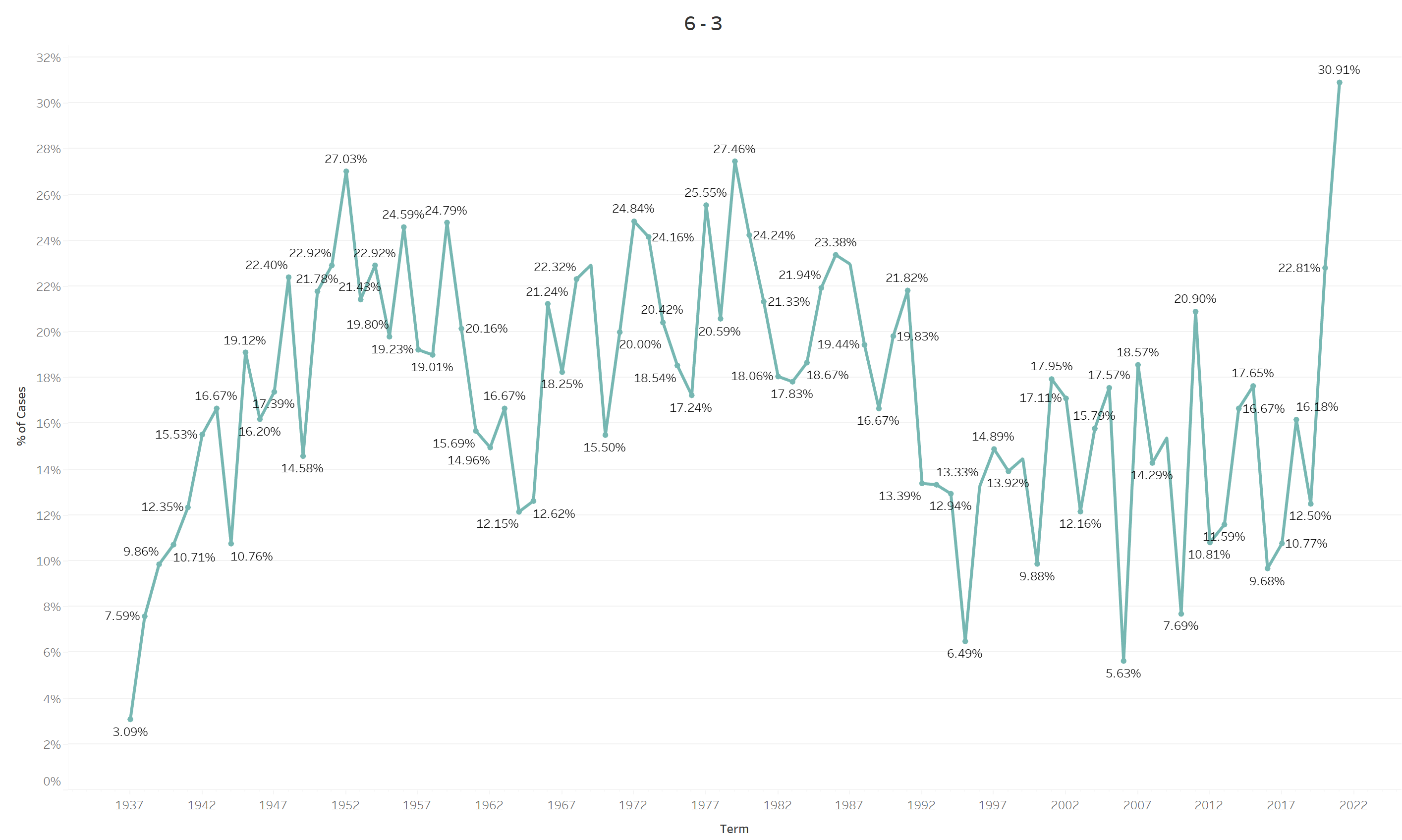

following

graph

shows

the

percentage

of

5-4

votes

per

term

since

1936:

The

fluctuation

on

a

yearly

basis

in

5-4

decisions

is

illuminating.

It

shows

that

even

with

clearly

polarized

courts,

the

justices

did

not

always

split

5-4

with

the

same

frequency.

One

reason

for

this

recently

is

that

there

was

a

period

after

Justice

Scalia

died

where

the

Court

only

had

eight

members.

More

recently

with

the

addition

of

Justice

Barrett

replacing

Justice

Ginsburg,

the

center

of

the

Court

shifted

to

the

right

so

that

the

conservatives

now

have

a

6-3

majority.

From

an

ideology

score

perspective,

the

transition

looks

like

the

following:

The

more

progressive

justices

are

farther

from

the

center

of

the

graph

than

some

of

the

conservatives

like

Roberts

and

Kavanaugh.

The

visual

shift

in

the

balance

of

the

Court

from

when

Justice

Ginsburg

passed

away

and

was

replaced

with

Barrett

is

apparent

in

the

2020

graph

(note

that

the

2021

term

scores

are

not

yet

available).

This

should

have

impacted

the

justices’

voting

patterns.

In

particular

we

should

see

more

6-3

votes

and

fewer

5-4

votes

from

the

2020

term

forward.

This

is

known

as

a

supermajority

because

even

if

one

conservative

justice

defects

from

the

majority,

the

conservatives

still

can

secure

5-4

decisions

(think

of

Roberts

concurring

in

Dobbs

even

though

he

wouldn’t

have

overturned

Roe).

This

may

also

impact

decision

making

of

conservative

justices

on

the

fence

since

even

if

they

vote

along

with

the

three

other

justices

in

such

close

cases,

it

will

be

in

a

losing

effort.

The

current

Court

is

not

the

only

time

when

the

Court

has

had

a

6-3

ideological

balance

according

to

the

MQ

Scores,

although

this

may

be

one

of

the

strongest

6-3

formations

yet.

The

first

time

this

orientation

was

evident,

and

one

of

the

strongest

alliances

was

during

the

Hughes

Court

years.

Between

the

1936

and

1940

terms

the

ideological

makeup

of

the

Court

looks

like

the

following:

The

Court

had

10

members

in

the

1937

and

1938

terms

with

Justice

Sutherland

retiring

and

Justice

Reed’s

appointment.

Justice

Cardozo

passed

away

right

at

the

end

of

the

1937

term

and

was

replaced

by

Justice

Frankfurter.

Then

Justice

Brandeis

retired

in

the

middle

of

the

1938

term

and

was

replaced

by

Justice

Douglas.

Justice

O.

Roberts

score

for

the

1937

term

was

just

barely

positive

at

.015

but

became

more

so

in

1938

with

.352.

Along

with

Justices

McReynolds

and

Butler,

Justice

O.

Roberts

makes

up

the

conservative

trio

for

these

two

years.

When

Justice

Butler

passed

away

during

the

1939

term

he

was

replaced

with

the

more

liberal

Justice

Murphy.

At

this

point

Chief

Justice

Hughes

pivots

to

the

right

and

joins

Justices

Roberts

and

McReynolds

on

the

right

of

the

Court.

Under

the

end

of

Chief

Justice

Vinson’s

tenure

and

the

beginning

of

Chief

Justice

Warren’s,

the

ideological

supermajority

shifted

in

the

opposite

direction.

In

1949

Justices

Black

and

Douglas

were

the

only

two

justices

on

the

left

of

the

Court

and

there

was

a

significant

distance

between

those

justices

and

Justice

Frankfurter

who

is

the

next

justice

along

the

ideological

map.

Frankfurter

wavered

a

little

closer

to

left

in

the

next

three

terms

yet

moved

back

to

the

left

when

Justice

Warren

joined

the

Court

in

the

1953

term.

Justice

Warren

then

became

the

third

justice

on

the

left

in

1954.

Fast

forward

almost

two

decades

to

the

Burger

Court

and

another

6-3

formation

takes

root.

Justices

Marshall,

Brennan

(whose

ideological

position

is

covered

by

Justice

Marshall’s

in

1972),

and

Douglas

make

up

the

liberal

bloc

for

these

three

terms.

Justice

Stewart

was

close

to

the

ideological

center

in

the

1972

term

and

pushed

a

bit

farther

to

the

right

in

1973

and

1974.

Lastly,

an

ideologically

conservative

supermajority

was

present

in

the

early

Rehnquist

Court

years.

The

Court’s

left

was

composed

of

Justices

Blackmun,

Stevens

and

Marshall

in

1990.

Justice

Souter

starts

out

on

the

conservative

end

of

the

Court

when

he

is

appointed

in

1990

but

shifts

to

the

left

in

the

1991

and

1992

terms.

When

Justice

T.

Marshall

passes

away

at

the

beginning

of

the

1991

term,

he

is

replaced

by

Justice

Thomas

which

pushes

the

pendulum

even

farther

to

the

right.

Comparisons

That

brings

us

to

the

modern

supermajority

of

Justices

Thomas,

J.

Roberts,

Alito,

Gorsuch,

Kavanaugh,

and

Barrett.

So

how

does

the

strength

of

the

current

Court’s

makeup

compare

to

those

of

the

past?

One

way

to

think

of

this

is

through

the

percentage

of

6-3

rulings

across

each

term.

According

to

these

percentages,

the

2021

term

had

the

highest

percentage

of

6-3

decisions

across

cases

that

went

to

oral

argument

since

at

least

the

1937

Term

(which

is

as

far

as

the

MQ

Scores

go).

Diving

a

bit

deeper

into

the

data

though

a

different

story

appears.

The

6-3

decisions

in

the

above

graph

do

not

capture

the

percentage

of

6-3

decisions

across

ideological

lines.

Unanimous

decisions

also

do

not

capture

ideological

differences,

so

instead

we

can

focus

on

the

percentage

of

6-3

ideological,

non-unanimous

decisions

in

these

terms.

When

Justice

Barrett

joined

the

Court

in

the

2020

term

the

percentage

of

6-3

ideological

decisions

in

argued

non-unanimous

decisions

was

27.6%.

This

jumped

up

to

29.5%

in

the

2021

term.

The

greatest

percentages

of

6-3

ideological

decisions

were

in

the

Hughes

Court

years

though.

In

two

terms,

1937

and

1940,

the

Court

saw

6-3

ideologically

split

decisions

in

35.6%

of

the

Court’s

non-unanimous

decisions.

The

major

difference

between

now

and

in

the

past

is

the

staying

power

of

the

current

ideological

bloc.

Prior

to

this

term,

such

supermajorities

did

not

remain

stable

over

more

than

a

couple

of

terms.

The

current

supermajority

is

poised

to

do

just

that.

With

Justice

Thomas

as

the

oldest

justice

at

74

years

of

age,

this

Court

can

potentially

stay

as

currently

composed

for

another

decade

or

more.

If

the

Court’s

oldest

justices,

Thomas

and

Alito

are

strategic

about

their

retirements,

so

that

their

seats

are

replaced

by

Republican

Presidents,

and

no

justices

pass

away

unexpectedly,

this

conservative

Court

could

potentially

retain

its

strength

much

farther

in

the

future.

Read

more

at

Empirical

SCOTUS….

Adam

Feldman

runs

the

litigation

consulting

company

Optimized

Legal

Solutions

LLC.

For

more

information

write

Adam

at adam@feldmannet.com. Find

him

on

Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.