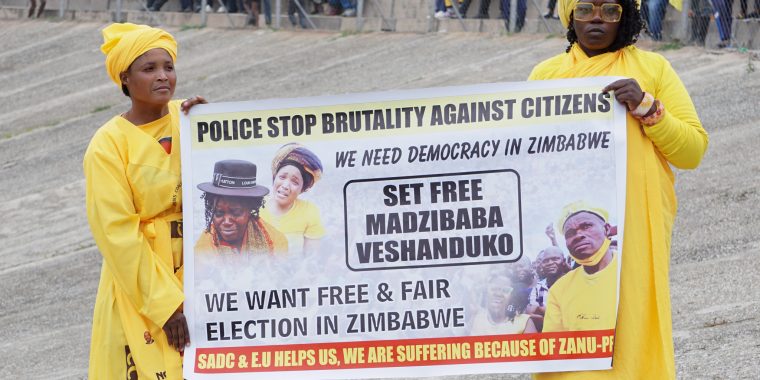

Precious

Dinha,

left,

holds

a

banner

at

a

rally

in

Mutare,

Zimbabwe,

on

March

19,

2022,

for

opposition

presidential

candidate

Nelson

Chamisa.

Photo

Credit:

Evidence

Chenjerai,

Global

Press

Journal

Zimbabwe

Evidence

Chenjerai,

Global

Press

Journal

Zimbabwe

This

story

was

originally

published

by

Global

Press

Journal.

MUTARE,

ZIMBABWE

—

Precious

Dinha

elbows

her

way

into

a

packed

soccer

stadium.

Despite

thunderclouds

looming

above,

thousands

of

yellow-clad

Zimbabweans

are

singing,

dancing

and

thrusting

their

index

fingers

skyward.

They

wave

placards

in

Shona

and

English

saying,

“We

need

democracy

in

Zimbabwe”

and

“Police

stop

brutality

against

citizens.”

Dinha

unfurls

her

own

large

white

banner:

“We

want

free

and

fair

elections.”

Soon

Zimbabwe’s

leading

opposition

presidential

candidate,

44-year-old

Nelson

Chamisa,

bounds

onto

a

stage.

“Do

you

embrace

the

new?”

he

asks.

“Yes!”

the

crowd

shouts.

Dinha

traveled

close

to

four

hours

from

Harare,

the

capital,

to

hear

Chamisa

speak.

She

attends

every

Chamisa

rally

she

can,

wearing

yellow,

the

color

of

his

movement,

and

reveling

in

the

festive

atmosphere.

This

event

marks

the

formal

introduction

of

his

new

political

party,

Citizens

Coalition

for

Change

(CCC),

in

eastern

Zimbabwe

ahead

of

next

year’s

presidential

election.

Dinha,

32,

believes

Chamisa’s

relative

youth

and

outsider

perspective

can

help

resuscitate

Zimbabwe’s

listless

economy,

with

high

levels

of

unemployment,

inflation

and

food

insecurity.

“I

have

never

been

employed

despite

having

professional

qualifications.

I

do

not

even

know

what

a

pay

slip

looks

like,”

Dinha

says.

She

was

trained

as

a

human

resources

manager

but

raises

chickens

and

sells

secondhand

clothes

to

get

by.

“He

understands

us

as

youths,

and

there

are

promises

of

reviving

the

economy

so

that

we

can

also

have

jobs.”

Despite

his

supporters’

fervency,

Chamisa

faces

a

tough

road

to

the

presidency.

In

2018,

he

lost

a

bid

to

wrest

control

from

the

Zimbabwe

African

National

Union-Patriotic

Front

(ZANU-PF),

the

ruling

party

since

1980,

in

an

election

whose

fairness

an

international

election

monitoring

team

questioned.

But

in

the

years

since,

other

southern

African

opposition

leaders

have

found

success

in

copying

the

Chamisa

playbook:

targeting

young,

social

media-savvy

voters

fed

up

with

entrenched

parties

and

alleged

corruption.

Chamisa

supporters

believe

recent

upstart

victories

in

Malawi

and

Zambia

could

foreshadow

his

own.

“2022

is

the

year

when

change

in

Zimbabwe

was

authored

by

God,”

he

tells

the

rally

crowd.

“No

one

can

stop

an

idea

whose

time

has

come.”

With

little

public

polling

in

Zimbabwe,

it’s

hard

to

assess

his

chances.

Mike

Bimha,

ZANU-PF’s

secretary

for

commissariat,

dismisses

Chamisa

as

an

electoral

threat.

“It

is

still

an

opposition

which

came

out

of

forces

from

outside

Zimbabwe

who

want

a

regime

change,”

Bimha

says.

Chamisa

stumbled

into

the

political

spotlight.

In

2018,

Zimbabweans

had

just

witnessed

the

ouster

of

their

longtime

leader,

Robert

Mugabe,

in

a

military

coup.

As

the

new

president,

Emmerson

Mnangagwa

vowed

to

modernize

the

health

care

system,

repair

crumbling

infrastructure

and

rebuild

frayed

business

ties

with

Europe.

He

expected

to

face

the

popular

opposition

candidate

Morgan

Tsvangirai

in

that

July’s

presidential

election,

but

just

months

before

the

vote,

Tsvangirai

died

of

complications

related

to

cancer.

Chamisa

stepped

in.

A

former

student

activist

and

member

of

Parliament,

Chamisa

found

ways

to

sidestep

government-controlled

media

outlets

and

drum

up

support.

He

electrified

crowds

around

the

country

with

rallies

that

enhanced

his

name

recognition

and

built

community

among

his

backers,

and

wooed

voters

directly

on

social

media.

(He

now

has

1

million

Twitter

followers.)

Nevertheless,

Zimbabwe’s

first

post-Mugabe

election

ended

in

turmoil,

with

vote-rigging

allegations

and

protests

where

security

forces

fired

into

crowds

and

several

people

died.

The

Zimbabwe

Electoral

Commission

—

long

criticized

by

opposition

parties

as

an

arm

of

ZANU-PF

—

eventually

declared

Mnangagwa

the

winner

with

50.8%

of

the

vote.

Afterward,

the

Zimbabwe

International

Election

Observation

Mission,

a

group

of

international

election

observers,

denounced

the

process,

saying

Zimbabwe

lacked

“a

tolerant,

democratic

culture”

where

“parties

are

treated

equitably

and

citizens

can

cast

their

vote

freely.”

A

Zimbabwe

Electoral

Commission

spokesperson

didn’t

respond

to

requests

for

comment.

Bimha,

the

ZANU-PF

official,

says,

“We

want

free

and

fair

elections,

harmony,

love

and

collaboration,

and

that

is

a

party

position.”

Elsewhere

in

the

region,

many

voters

shared

the

frustrations

of

Chamisa

supporters,

says

political

analyst

Onai

Moyo,

believing

that

the

leaders

who

freed

their

countries

from

colonialism

had

subsequently

failed

at

governing.

In

2020,

Lazarus

Chakwera

won

the

presidency

in

Malawi.

In

2021,

Hakainde

Hichilema

clinched

victory

in

Zambia.

Both

opposition

candidates

rallied

voters

with

a

Chamisa-esque

message

of

African

renaissance.

Their

argument:

The

ruling

class

had

fallen

prey

to

corruption,

leaving

the

continent

poor

and

underdeveloped

despite

its

vast

natural

resources.

In

Zimbabwe,

that

message

has

gained

traction

even

with

older

voters.

Cresencia

Chabuka,

61,

was

a

senator

with

Chamisa’s

old

political

coalition,

the

Movement

for

Democratic

Change

Alliance.

She

joined

Chamisa’s

new

party,

she

says,

because

pensioners

like

her

are

suffering

from

poverty

as

hyperinflation

erodes

their

savings.

At

the

soccer

stadium

rally,

she

flits

through

the

crowd,

trying

to

convince

her

peers

that

Chamisa

is

the

solution.

“A

lot

of

senior

citizens

have

lost

faith

in

ZANU

promises,”

she

says.

Even

so,

there

are

key

differences

between

Zimbabwe

and

its

neighbors.

For

example,

since

liberation

in

the

1960s,

Zambians

have

chosen

four

different

political

parties

to

run

the

country.

Each

ruled

for

many

years,

but

the

periodic

change

in

leadership

meant

Zambia’s

election

system

wasn’t

intertwined

with

a

single

party,

Moyo

says.

In

Zimbabwe,

one

party

—

and

mainly

one

man

—

was

in

charge.

ZANU-PF

was

instrumental

in

overthrowing

white-minority

rule

in

the

1970s,

a

campaign

that

was

bloodier

than

in

either

Zambia

or

Malawi.

“Zimbabwe’s

independence

came

through

a

liberation

struggle,”

says

political

analyst

Alexander

Rusero.

“It

came

at

the

bedrock

of

massive

violence

of

several

forms,

coupled

with

inflicting

pain

and

fear

in

the

masses.”

To

party

loyalists,

ZANU-PF

has

earned

the

right

to

lead

Zimbabwe.

“Nyika

inotongwa

nevene

vayo,”

they

say

in

Shona

—

only

the

liberators

can

rule.

Even

voters

fed

up

with

the

ruling

class

may

not

rally

for

Chamisa.

Tendai,

47,

who

asked

to

be

identified

only

by

his

first

name

because

of

Zimbabwe’s

history

of

political

violence,

lives

in

Mutare

and

scrapes

by

on

gardening

jobs.

He

voted

for

ZANU-PF

in

2018,

hoping

for

an

economic

revival

that

never

arrived.

While

he’s

lost

faith

in

Mnangagwa,

he

doesn’t

view

Chamisa

as

a

viable

alternative.

“Once

you

vote

them

into

power,

they

serve

self-interests

and

forget

us,”

Tendai

says.

He

plans

to

stay

home

instead

of

voting.

This

March,

Zimbabwe

held

elections

for

various

parliamentary

and

council

seats.

They

did

not

bode

well

for

Chamisa’s

party.

Before

the

vote,

Vice

President

Constantino

Chiwenga

vowed

that

ZANU-PF

would

defeat

CCC

—

something

he

compared

to

crushing

lice.

The

next

day,

a

Chamisa

supporter

was

fatally

stabbed

at

a

rally.

Though

Chamisa’s

party

won

a

majority

of

contested

seats,

most

were

already

in

the

hands

of

opposition

candidates;

ZANU-PF

even

recovered

two

seats

it

had

lost

in

previous

contests.

Chamisa

often

promises

electoral

reforms

in

his

speeches,

but

his

allies

don’t

have

the

numbers

in

Parliament

to

make

changes

before

the

next

election.

“We

are

likely

to

have

history

repeating

itself

when

it

comes

to

violence,”

Rusero

says.

“I

also

don’t

see

the

elections

bringing

the

much-needed

change,

instead

worsening

the

situation

and

deepening

the

divide

that

exists

among

Zimbabweans.”

At

the

soccer

stadium

rally,

Dinha

is

more

optimistic.

A

devout

Christian,

she

sees

Chamisa

as

a

Moses-like

figure,

tasked

with

leading

Zimbabwe

to

a

political

promised

land.

All

around

her,

supporters

sweat

out

the

three-hour

rally;

some

had

climbed

trees

outside

the

stadium

to

get

a

better

glimpse

of

the

candidate.

Others

raise

placards

saying,

“ngaapinde

hake

mukomana”

—

let

the

boy

rule.

Evidence

Chenjerai

is

a

Global

Press

Journal

reporter

based

in

Mutare,

Zimbabwe.

Post

published

in:

Featured