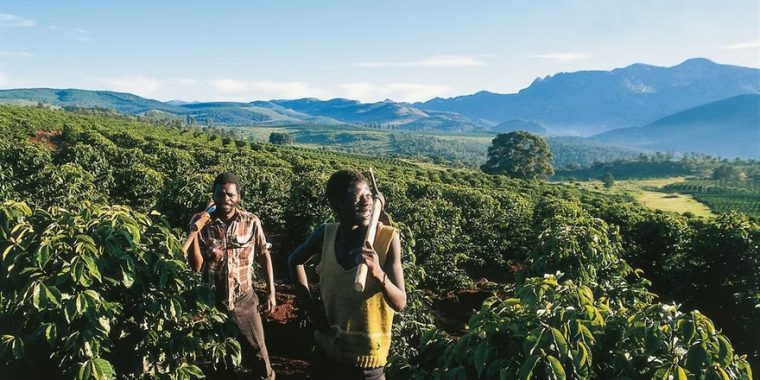

Nespresso

is

supporting

small

coffee

bean

farmers

as

part

of

the

government’s

plan

to

revive

the

once

flourishing

industry. Deagostini

/

Alamy

Stock

Photo

Twenty-three

years

ago,

forced

evictions

of

white

coffee

farmers

from

Zimbabwe

led

to

the

collapse

of

the

industry.

Today

coffee

production

is

on

the

rise,

with

the

support

of

Nestlé’s

Nespresso

brand,

but

it

is

still

a

fraction

of

what

it

used

to

be.

David

Muganyura,

a

veteran

coffee

farmer,

joined

a

Nespresso

initiative

that

seeks

to

revive

growing

of

the

crop

at

its

launch

in

2019.

He

has

not

looked

back

since.

The

74-year-old

who

had

been

farming

the

bean

since

1984

saw

his

output

and

profitability

collapse

to

near

zero

by

forced

evictions

of

the

main

coffee

growers

of

the

country

back

in

2000.

This

led

to

a

decline

in

export

demand

for

the

locally

grown

crop.

In

2000,

the

price

of

the

crop

dropped

to

as

low

as

$0.20

(CHF0.18)

per

kilogram.

Coffee

farmer

David

Muganyura

and

his

wife

Fatima

Matimbe

on

their

coffee

plantation

in

the

Honde

Valley

in

eastern

Zimbabwe. Daisy

Jeremani

So

when

Nestlé

introduced

its

Tamuka

MuZimbabwe

programme

(indigenous

Shona

language

for

“we

have

awakened

in

Zimbabwe”)

to

reboot

coffee

growing,

he

was

among

the

first

to

sign

on.

The

programme

included

a

training

run

by

Lausanne-based

coffee

giant

Nespresso,

owned

by

Nestlé,

through

a

local

initiative

called

TechnoServe

in

2018.

It

also

included

the

Swiss

company

buying

his

coffee

beans

at

a

producer

price

of

about

$8

per

kilogram.

This

is

almost

double

what

local buyers,

such

as

Cairns

Foods

and

Grain

Marketing

Board

pay

for

the

crop.

Muganyura

was

among

the

first

locals

to

plant

the

coffee

seeds

under

the

initiative

a

year

later.

He

doubled

output

to

about

1,500

kg

in

that

first

year,

earning

approximately

$10,000.

The

average

salary

in

Zimbabwe

was

$220

a

month

in

2022.

“We

have,

through

the

proceeds

we

get

from

the

partnership,

invested

in

other

farming

projects,

been

able

to

pay

for

health

care

for

their

family,

repay

loans

for

inputs

and

paying

farm

workers. We

have

also

settled

the

debts

we

had

at

Zimbabwe

Coffee

Mill

[where

coffee

beans

are

processed],” he

told

SWI

swissinfo.ch.

The

Nespresso

initiative

falls

under

the

company’s

bigger

agenda,

AAA

Sustainable

Quality

programme

which

aims

to

revive

high

quality

coffee

production

in

different

regions

of

the

world

where

production

has

been

affected

by

conflict,

economic

or

environmental

disasters.

These

include

Colombia,

Puerto

Rico,

Cuba,

Uganda

and

the

Democratic

Republic

of

the

Congo.

It

seeks

to

establish

long-term

partnerships

with

farmers

and

communities

to

rebuild

sustainable

coffee

production.

In

Zimbabwe,

Nespresso

partnered

with

an

American

non-governmental

organisation,

TechnoServe,

two

local

coffee

bean

farms

and

about

450

smallholder

farmers

in

Honde

Valley. The

area

that

stretches

into

neighbouring

Mozambique is

best

suited

for

growing

Arabica

coffee,

a

high-quality

bean

known

to

contain

less

caffeine

and

for

its

smoother

taste

than

the

cheaper

Robusta

bean.

Nespresso

says

since

2016

it

has

invested

CHF39million

(about

$42million)

into

the

Reviving

Origins

global

programme

through

its

funding

vehicle

called

the

Nespresso

Sustainability

Innovation

Fund.

It

did

not

say

how

much

it

had

invested

in

Zimbabwe.

In

October

2022,

it

announced

an

additional

investment

of

$

4.5

million

into

Reviving

Origins

in

Africa.

Rising

from

the

ashes

Nespresso’s

initiative

is

part

of

a

larger

plan

by

the

Zimbabwe

government

to

revive

its

once

flourishing

coffee

industry

decimated

from

2000

onwards

when

Robert

Mugabe,

then

Zimbabwe’s

president,

authorised

evictions

of

the

up

to

4,000

large-scale

white

farmers

from

about

11

million

hectares

across

the

country.

Among

the

displaced

were

local

coffee

producers. Until

the

early

2000s,

the

country

was

among

the

top

30

growing

nations

globally,

producing

an

average

15,000

tonnes

of

the

crop

yearly. Now

annual

output

averages

500

tonnes

from

two

commercial

estates

and

some

450

small farms

of

around

2

hectares,

like

Muganyura’s

plantation.

By

2019,

smallholder

coffee

farming

had

essentially

collapsed,

as

most

black farmers

opted

for

better

paying

cash crops

such

as

macadamia

nuts.

In

2018,

the

government

launched

a

strategy

which

seeks

to

boost

coffee

output

to

10,000

tonnes

by

2024. The

plan

will

require

an

investment

of

$60

million

spread

over

five

years

to

maintain

existing

coffee

farms

and establish

4,700

hectares

of

new

plantations.

The

government

also

hopes

to

establish

a

sustainable

funding

model

for

the

crop.

A

government

agronomist

for

Mutasa

District,

Abraham

Mutsenura,

says

the

situation

for

smallholders

is

now

improving

with

more

farmers

growing

coffee

again.

But

he

adds,

the

industry

can

still

improve

both

the

quality

and

quantity

of

the

beans.

Annual

production

is

still

only

a

fraction

of

what

it

used

to

be.

The

government

now

prefers

to

push

crops

that

are

deemed

as

more

strategic

such

as

maize,

corn

or

soy.

With

no

proper

government

support,

challenges

remain

for

farmers.

The development

of

the

region

is

dependent

on

Nespresso.

There

is

no

other

local

initiative.

“The

Nespresso

initiative

has

resulted

in

some

positive

changes

to

their

farming

ventures,

but

there

is

a

need

for

constant

reviewing

of

the

market

price

of

the

bean

to

match

the

cost

of

production,”

he

says.

The

cost

of

chemicals

and

fertilisers

rise

every

season;

for

example

a

bag

of

ammonium

nitrate

cost

$94

in

2022

against

$55

in

2021.

More

Why

Switzerland

needs

workers

from

abroad

Switzerland

is

an

attractive

place

to

work

and

the

country

needs

specialists.

But

work

permits

can

be

hard

to

come

by.

Muganyura

adds

that

in

his

view

Nespresso

can

do

more

to

support

local

farming,

including

further

incentives

to

boost

the

size

of

the

land

farmed.

This

would

include

providing

farmers

with

more

resources

such

as

seeds

and

fertilisers.

He

also

stressed

the

importance

of

investing

in

irrigation

systems

in

the

country’s

main

coffee-growing

districts.

Coffee

farmer

David

Muganyuri

working

on

his

farm

in

the

Honde

Valley

in

eastern

Zimbabwe. Daisy

Jeremani

“A

strong

market

and

supply

relationship

is

key

for

the

mutual

sustainability

in

the

medium-

to

long-term

journey

(between)

Nespresso

and

TechnoServe

(and)

smallholder

farmers,”

he

says.

Nespresso

SA

global

public

relations

manager Delphine

Bourseau

acknowledged

that

the

initiative

has

to

contend

with

some

risks.

Reviving

Origins

is

a

long-term

programme

which

aims

to

overcome

diverse

local

challenges

which

previously

affected

coffee

production,

she

says.

“Each

area

has

been

chosen

specifically

because

it

was

under

environmental,

social

or

economic

factors

that

have

caused

a

drastic

reduction

of

production

of

coffee

in

the

area,”

she

tells

SWI

swissinfo.ch.

“As

a

result

of

the

differing

circumstances

affecting

these

communities,

each

Reviving

Origins

coffees

require

a

bespoke

approach,

and

we

focus

on

investing

in

a

smaller

number

of

communities

over

a

longer

period.

However,

due

to

the

complexity

of

these

projects

it

can

be

challenging

to

guarantee

exactly

when

and

what

the

results

will

be.”

Adding

to

farmers’

uncertainty

is

the

legal

obligation

for

them

to

cede

a

certain

percentage

of

their

earnings

to

the

Reserve

Bank

of

Zimbabwe. In

2019

and

2020

the

government

collected

20%

of

farmers’

proceeds.

In

2022 the

threshold

was

increased

to

40%. After

backlash

from

farmers

the

percentage

could

be

cut

to

25%

for

2023.

Edward

Dune,

former

vice

president

of

the

Zimbabwe

National

Farmers’

Union

sees

no

problem

with

the

government

not

supporting

the

production

of

coffee,

as

it

does

the

other

crops.

Coffee

farmers,

he

says,

have

the

option

of

accessing

commercial

loans

from

financial

institutions.

He

also

suggests

Nespresso

could

play

a

more

pivotal

role.

“The

government’s

role

is

basically

policy

development

and

if

they

have

done

something

towards

strategy,

the

improvement

of

productivity

along

the

value

chain,

then

they

have

done

more

than

enough,”

he

says.

Caleb

Mahoya,

head

of

the

Coffee

Research

Institute

based

in

the

southeastern

town

of

Chipinge,

told

SWI

swissinfo.ch

that

the

government

is

implementing

the

plan.

But

it’s

still

too

early

to

say

whether

its

growth

projections

will

be

met.

“We

will

only

be

clear

after

this

and

next

season

to

see

if

we

are

able

to

meet

that

target,”

he

says.

“We

have

new

farmers

each

and

every

year

and

they

will

add

to

the

achievement

of

this

target.”

–

SWI

swissinfo.ch

Post

published

in:

Agriculture